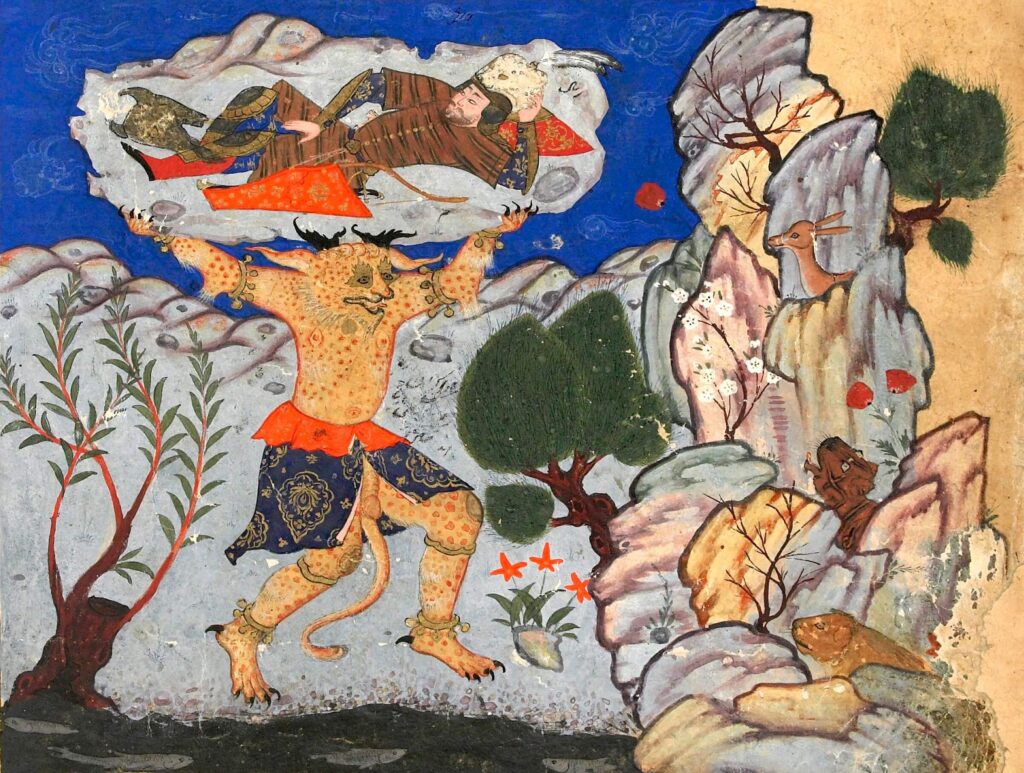

The Khevsur cosmogony1 starts with the battle of “the Children of God”/ “ღვთისშვილნი” against the Devis. “The supreme God”/ “მორიგე ღმერთი”2 sends his children down to earth, so they help the Khevsurians to claim property on the Caucasian highlands. Those lands are inhabited by beings called “Devis”/ “დევი”. The Devis are ambiguous creatures, who seem to be in complex relationships with the local humans. Some are friends with them and others will have them for dinner. The Devis are big, strong and wild. “The children of God”, who help the Khevsurs, on the other hand, carry angel-like properties. They are warriors of God, who fight in the name of a higher spirit, the God in the heavens.

The Khevsurs are pagan people. They worship pre-Christian indigenous deities. It is interesting though, how we find treats within Khesvur beliefs, that are typical for monotheistic religions, such as a strong hierarchy and a concept of evil versus good. The killing of the Devis is justified by their wild nature and their wickedness.3 Even though the Devis are often mentioned in the Khevsur cosmogony and also broadly in Georgian folklore, we don’t know much more about them other than their bad reputation, that stems from an antagonising human viewpoint. So let’s dig a bit deeper. Etymologically the word “Devi” derives from the Zoroastrian “Daevas”, cited as evil forces in the Zoroastrian religious texts called Avestas. If we trace the word even further back we find, that the Zoroastrian “Daevas” – the demons – and the Indian “Devis/ Devas” – the Gods – share origins. So let’s explore together and trace this wild ride from “God” to “Demon”.

War against the Devis and the Seizing of their Lands

To understand the Georgian “Devis” we need to start with the Khesvur cosmogony. The “Children of God” descend to earth with the aim to help the Khevsurs in securing property on Caucasian mountainous lands.4 They battle the Devis and demolish their houses. The ruins will become new homes for the Khevsurs and the battlefields will become sacred sites for worshipping the new Gods. As the ethnologist Z. Kiknadze states, the children of God “earn property for the Khevsurs by shedding blood”.5 The places of these warfares are not only loaded with legendary but also with sacred significance. In the Khevsuretian legacy texts called “Andrezi”6 the stories contain specific naming of places with great geographical precision, so that one could use the texts as a travel map and trace the places of the battles and other mysteries.7

Who are the Devis?

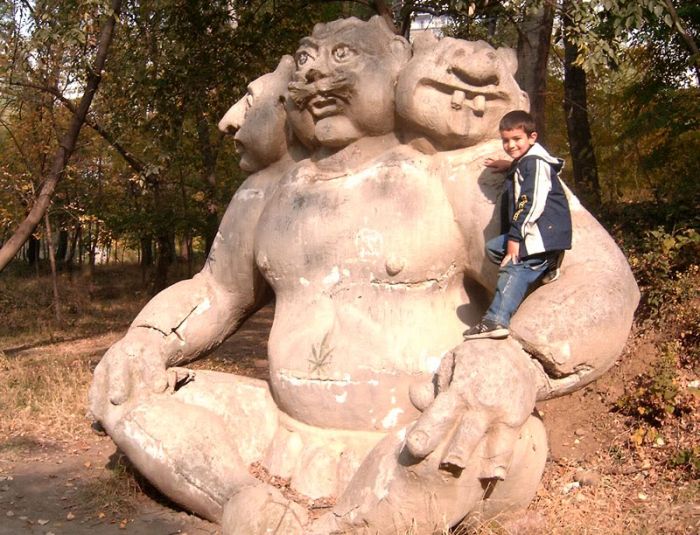

The Devis are partly humanoid and partly zoomorphic creatures. They share treats with the humans, like walking on two legs, having similar facial features, living in communities and ritualising social interactions. The Devis are much bigger in size, though, and therefore often described as giants. They have horns and strong body hair. In the more mythologised folk tales they are attributed with multiple heads and reversed feet.8

The legacy texts “Andrezi” and the ruined “giant’s villages” in the Pshav-Khevsureti mountains suggest, that the Devis were a group of real people who housed in neighbouring villages from the Khevsurs in the Caucasian highlands. The anthropologist T. Ochiauri highlights especially the areas of the Roshka gorge, Gudamakari-Pshav borders, Shuapkho-Magharoskari and etc.9 The ethnographic documentations of anthropological expeditions in the mentioned regions describe the ruined villages. They are built with massive stone and remind one of desolate giant’s dwellings.10

Complex Devi-Human Relationships

The Devis had a strong sense of community. They lived in families, had parents, marital partners and children.11 They celebrated weddings and festivities, just like the humans. Devis were involved in agriculture, owned fields, cattle and sheep.12 But above all they were particularly known for excellent blacksmithing crafts. In fact their black-smithery was greatly desired by the humans. We read in the texts about the human’s dilemma between their need of the Devi’s exquisite tools and their hurt human pride. The Devis are not willing to share their crafting knowledge with the humans, which creates a power dynamic. In the texts this relational dynamic is interpreted as an attempt to enslave the humans and make them ever dependent on their craft.13 The concern grows even more, as the Devis allow only women into their dwellings to buy their tools. 14 Men are not allowed into the Devi’s homes.

The human’s resentment towards the Devis grow. Their stories suggest, that the Devi’s take their women forcefully. Interestingly enough we read about occurrences though, where women seem to go to them out of their free will. Nevertheless, the story uses words, that suggest the Devi’s malicious attempts. In one legacy text we read: “They [Devis] tortured the women. They tempted them so much [with the beauty of the crafts], that the women ran to them.”15 Even though this story aims to tell about the wickedness of the Devis, it evokes a desire to question the assumptions of the narrator. As the story is neither told by the Devis nor by the women themselves.

There are many stories that foreground the adversary relationship between the Devis and the humans. One story highlights this in particular. In this story a Devi has a human wife with whom they bear many children. Out of disgust towards the interbreeding, the Khevsurs kill their whole offspring. The Devi turns berserk and curses the murderer, that he will hunt his descendants down for seven generations.16 This and other stories showcase relational behaviours between these two groups, that are characterised with violence and with the “othering” of the “stranger” group.

Devis as the highland’s indigenous people?

Let’s imagine for a moment, that the Devis were real people. If so, they must have been an older, more indigenous, population of the Caucasian highlands. Why? Let’s explore.

1. According to the legacy texts the Khevsurs invoked the new Gods to help them with getting rid of the Devis. The “Supreme God” in the sky hears the Khevsurs prayer, and sends the “Children of God” at war against the Devis.17 The Devis are mentioned as “Dev-Kerpebi”/ “დევ-კერპები”, which can be translated as “Devi-icons”. The Devi icon’s are contrasted to the Khevsur’s new Gods, that are referred to as crosses – “Djvrebi”/ “ჯვრები”. The anthropologist Z. Kiknadze writes: “the cross – is the symbol for a new religion, that demolishes old temples and is raised instead of them.”18 This suggests that the Devis were revering older Gods, hinting to their preceding connection with the land.

2. Devis were agricultural settlers and excellent craftsmen in blacksmithery. This connotes, that they were not only fresh settlers of the Caucasian mountains, but must have had also a great knowledge about the land. Skilful black-smithery requires a long tradition of mastery, that is acquired through the familiarity with the used material and its land. You’d need to mine the right places and process the metal with special techniques gained over time, which implies a strong connection with the place.

3. The Devis and the humans are not integrated communities, but rather estranged towards each other. That suggests, that one of the people must have been newbies to the land. The Devi’s old Gods get replaced by the Khevsur’s new Gods – the “Cross-Shrines”/ “ჯვარ-ხატები”, which points to the Khevsurs as the new settlers.

The information we have about the Devis comes from the side that partook in extirpating them. Nevertheless, we can understand more about them by following the word Devi. “Devi” must have been a name, that was assigned to them by the humans. By exploring the meaning of that name, we can speculate about the reasons of why they might have been called so. Therefore, let’s explore the history of the word “Devi”.

Etymology of the word Devi

The word “Devi” derives from the Persian word “Daeva”, which refers to the powers antagonising the Zoroastrian God of the sky Ahura Mazda.19 “The daevas are a class of beings mentioned repeatedly throughout the Avesta and the later Zoroastrian texts. The word daeva and its derivatives – including the Old Iranian daiva, Pahlavi dew, and later Persian div – always carries a negative connotation, meaning false god or, in later texts especially, demon […] However, the word daeva also bears linguistic relationship to the Sanskrit word deva, referring to one of the principal classes of gods”20.

On the Xerxes daiva inscription, dating back to the 5th century BCE, we find the word “daiva” occurring several times. Xerxes was a Persian ruler and a follower of the Zoroastrian God Ahura Mazda. In the Encyclopaedia Iranica C. Herrenschmidt and J. Kellens investigate the meaning of the “daivas” in the inscriptions. There Xerxes announces his deeds of destroying old worshipping sites of the daivas in the name of Ahura Mazda. “He [Xerxes] put down the rebels and restored the country to its former condition. If the country “in revolt” could be equated with the country where false daivas had been worshiped, it would follow that Xerxes understood daiva- in the Younger Avestan sense “god of another religion””.21

Who were the “other gods”, that got banished by the Zoroastrian followers?

Who are the “other Gods”?

Zoroastrianism is the first known monotheistic belief system and it predates the Abrahamic religions. It is characterised by a strongly dualistic doctrine of good versus evil. The Vendidad is a collection of late Avestan texts, that deal with the various manifestations of the daevas. In Vendidad 1022 and 1923 three divinities of the Vedic pantheon follow Angra Mainyu, the “great enemy” of the Zoroastrian God Ahura Mazda. These divinities are Indra, Rudra (mentioned as Sarva) and Nasatya (mentioned as Nanghaithya). Together with three other daevas the six “evil” oppose the six Amesha Spentas – the six manifestations of Ahura Mazda.

Let’s focus especially on one of the mentioned daevas: Rudra. Rudra is a Rigvedic deity associated with Shiva. Stella Kramrisch suggests the etymological connection of the adjectival form raudra, which means ‘wild’, i.e., of rude (untamed) nature, and translates the name Rudra as ‘the wild one’ or ‘the fierce god’.” 24 “Rudra is called ‘the archer’ (Sanskrit: Śarva) and the arrow is an essential attribute of Rudra. This name appears in the Shiva Sahasranama, and R. K. Śarmā notes that it is used as a name of Shiva often in later languages.”25

Conclusions

We see, that the Georgian Devi goes back to the Persian Daeva – the Demons -, which in turn is traceable to the Vedic Devas – the Gods. It is ironic that the untamed and wild Rudra, a form of Shiva, is demonised in the Zoroastrian religion. The Zoroastrian influence on Caucasian groups such as the Khevsurs get translated into their behaviour towards the Devis. They name them Devis, the people who worship other, older Gods, they demonise and extinguish them. If the Devis were a group of people, who revered old(er) Gods, then it would be interesting to inquire about who those Gods were. Even though, we traced the word Devi back to the Vedic deities, this doesn’t necessitate concluding, that they worshipped Hindu Gods. As the word was derived from the Persian Daeva, it must have been used in the context of Zoroastrian culture. Which means the name Devi was simply connoting to the meaning of “reverers of other Gods”. It is worthy inquiring though, who the “other Gods” or forces of those Caucasian prior settlers were. But let’s leave that inquiry for another time.

Sources & Remarks:

- Even though I refer to Khevsur origin stories as a “cosmogony”, it is more accurately a sociogony, as the origin stories circle around the creation of Khevsur communities and culture in the Caucasian highlands. See: Kiknadze Zurab, Georgian Mythology 1, Cross and its Community, Tbilisi 2016, pg. 17. ↩︎

- The Khevsuretian “pantheon” is characterised by a hierarchical order, in which the “supreme God” stands in the utter authority. His primary son Kviria/ კვირია is a deity of fertility and the vertical connector of the supreme God and earth. He is the only one who is allowed unconstrained and direct communion with his “father”. After him come the “Children of God”/ “ღვთისშვილნი”. They are angel-like creatures, who are responsible for the safety and wellness of the humans. A village is formed under the patronship of a given “Child of God”. For more info about Khevsurs and their cosmogony visit here. ↩︎

- Kiknadze Zurab, Georgian Mythology 1, Cross and its Community, Tbilisi 2016, pg. 18. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 18, 19. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 18. ↩︎

- Kiknadze Zurab, Andrezi, The Religious-Mythological Oral Traditions of the Highland of Eastern Georgia, Tbilisi 2009. ↩︎

- Which I did, by the way, in my research project about an ancient Khevsur prophetic profession called “Qadagi”. ↩︎

- Ochiauri Tina, Ancient Georgian Religions, Tbilisi 1954, pg. 166. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 23. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 24. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 32. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 25. ↩︎

- Kiknadze Zurab, Georgian Mythology 1, Cross and its Community, Tbilisi 2016, pg. 22. ↩︎

- Ochiauri Tina, Ancient Georgian Religions, Tbilisi 1954, pg. 28. ↩︎

- “ქალებს დაუწყეს წამებაი. ისე მახიბლეს, რო ქალებ თაო მირბოდეს იქისკე.” Ibid, pg. 39. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 34. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 39. ↩︎

- “ჯვარი – ახალი რელიგიის ნიშანი, ანგრევს საკერპოებს და აღიმართება მათ ადგილას” Kiknadze Zurab, Georgian Mythology 1, Cross and its Community, Tbilisi 2016, pg. 20. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 19. ↩︎

- Ghan Chris, The Davis in Zoroastrian Scripture, University of Missouri-Columbia 2014, pg. 5. ↩︎

- Herrenschmidt Clarisse and Kellens Jean, Encyclopaedia Iranica: https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/daiva-old-iranian-noun ↩︎

- Vendidad 10: http://www.avesta.org/vendidad/vd10sbe.htm ↩︎

- Vendidad 19: http://www.avesta.org/vendidad/vd19sbe.htm ↩︎

- Kramisch Stella, The Presence of Siva: https://books.google.co.in/books?id=O5BanndcIgUC&redir_esc=y ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudra#cite_ref-20 ↩︎